The Possibility of Evil: Exploring Hannah Arendt’s Concept

Hannah Arendt’s groundbreaking work delves into the unsettling notion that evil isn’t always monstrous, but can emerge from thoughtlessness and systemic structures.

Her analysis, sparked by the Eichmann trial, challenges conventional understandings of wickedness, prompting reflection on individual responsibility and bureaucratic complicity.

Exploring the “banality of evil” reveals how ordinary individuals can participate in horrific acts, not through inherent malice, but through a lack of critical thought.

The question of evil has haunted philosophical and theological discourse for centuries, yet remains profoundly relevant in the modern era. Hannah Arendt’s work offers a unique perspective, shifting focus from inherent wickedness to the conditions that allow evil to flourish.

Her exploration, born from observing the Eichmann trial, suggests evil isn’t solely perpetrated by monstrous individuals, but can arise from seemingly ordinary people operating within problematic systems. This challenges us to confront the unsettling “possibility of evil” within ourselves and society.

Arendt’s insights compel a re-evaluation of moral responsibility, urging critical examination of thoughtlessness and uncritical obedience, vital for preventing future atrocities.

Historical Context: The Eichmann Trial (1961)

Adolf Eichmann’s 1961 trial in Jerusalem served as the catalyst for Hannah Arendt’s seminal work on the “banality of evil.” Eichmann, a key architect of the Holocaust, wasn’t portrayed as a raging ideologue, but as a disturbingly ordinary bureaucrat.

Arendt’s reporting focused on Eichmann’s apparent thoughtlessness and lack of genuine malice, prompting her to question how such atrocities could be enacted by seemingly unremarkable individuals. The trial exposed the chilling efficiency of systemic evil.

This context profoundly shaped Arendt’s analysis, highlighting the dangers of uncritical obedience and bureaucratic indifference.

Understanding “The Banality of Evil”

Arendt’s concept describes how horrific acts can be committed by individuals who aren’t inherently evil, but rather, are thoughtless and obedient to systems.

It’s a disturbing realization that evil doesn’t always manifest as monstrous intent, but can arise from bureaucratic normalcy.

Defining the Banality of Evil

The banality of evil, a phrase coined by Hannah Arendt, doesn’t suggest evil is trivial, but rather that it can be perpetrated by seemingly ordinary individuals.

These individuals aren’t necessarily driven by deep-seated malice or ideological hatred, but instead, demonstrate a disturbing lack of critical thinking and moral reflection.

It’s a chilling realization that participation in evil deeds can stem from a simple failure to question authority or consider the consequences of one’s actions.

This concept highlights the danger of uncritical obedience and the importance of individual responsibility in preventing atrocities.

Eichmann as a Case Study

Adolf Eichmann, a key organizer of the Holocaust, became Hannah Arendt’s focal point for illustrating the “banality of evil” during his 1961 trial.

Arendt observed Eichmann not as a monstrous ideologue, but as a remarkably unremarkable bureaucrat, focused on efficiency and following orders.

He appeared disturbingly normal, lacking in deep conviction or personal hatred, simply fulfilling his assigned tasks within a horrific system.

This observation challenged the notion that evil requires extraordinary wickedness, suggesting it can be enacted by individuals devoid of profound malice.

Beyond Individual Malice: Systemic Evil

Arendt’s concept extends beyond attributing evil solely to individual perpetrators; she emphasizes the role of systemic structures in enabling atrocities.

The Holocaust wasn’t simply the result of Hitler’s malice, but a product of a bureaucratic machine that normalized horrific acts through compartmentalization and obedience.

This systemic evil diffuses responsibility, allowing individuals to participate in atrocities without confronting the full moral weight of their actions.

The focus shifts from individual wickedness to the dangers of uncritical obedience and the dehumanizing effects of bureaucratic processes.

Hannah Arendt’s Key Arguments

Arendt posited that thoughtlessness, the absence of critical reflection, is a crucial component enabling evil, alongside the dangers of bureaucratic structures and motives.

Thoughtlessness and Moral Responsibility

Arendt argued that a stunning lack of critical thinking—thoughtlessness—was a key factor in enabling Eichmann’s participation in the Holocaust. This wasn’t necessarily malice, but a failure to engage in moral reasoning, to question orders, or to consider the consequences of actions.

She emphasized that individuals are responsible for their actions, even within a system, and that the capacity for moral judgment requires active engagement with the world. Thoughtlessness allows individuals to become cogs in a machine, absolving themselves of personal accountability.

This concept challenges the notion that evil is solely perpetrated by inherently wicked individuals, highlighting the potential for ordinary people to commit atrocities through inaction and uncritical obedience.

The Absence of Motive

Arendt observed that Eichmann didn’t appear driven by a deep-seated hatred of Jews or a fervent ideological commitment; rather, he seemed motivated by careerism and a desire to fulfill his duties within the Nazi bureaucracy. This lack of a discernible, profound motive was deeply unsettling.

The “banality of evil” suggests that evil deeds aren’t always born of passionate conviction, but can stem from a chilling emptiness, a willingness to follow orders without moral reflection.

This absence of a clear motive complicates traditional understandings of evil, suggesting it can be perpetrated by individuals who are not necessarily monsters, but simply unthinking functionaries.

The Role of Bureaucracy in Facilitating Evil

Arendt highlighted how the Nazi bureaucracy provided a structure that enabled and even encouraged participation in evil acts. The compartmentalization of tasks, the emphasis on obedience, and the lack of individual accountability created a system where individuals could distance themselves from the moral implications of their actions.

This bureaucratic framework allowed for the efficient execution of horrific policies, shielding participants from direct responsibility and fostering a sense of normalcy within an inherently evil system.

The system itself, rather than individual malice, became a key facilitator of evil.

Criticisms and Controversies

Arendt’s work faced criticism, including accusations of sympathizing with Eichmann and downplaying intentionality. Debates arose concerning action versus intent, challenging her thesis.

Scholars questioned whether she adequately addressed the deep-seated antisemitism fueling the Holocaust.

Accusations of Sympathy for Eichmann

Arendt faced intense backlash, accused of exhibiting sympathy towards Adolf Eichmann, a key architect of the Holocaust. Critics argued her portrayal of him as a thoughtless bureaucrat minimized his culpability and the deliberate evil of his actions.

This perception stemmed from her focus on his “banality,” leading some to believe she downplayed his ideological commitment to Nazi ideology and antisemitism. The controversy ignited a fierce debate about the ethics of reporting on evil and the potential for misinterpretation.

Many felt she failed to adequately convey the profound moral gravity of his crimes, sparking lasting condemnation.

The Debate Over Intent vs. Action

Arendt’s thesis ignited a crucial debate: does evil require malicious intent, or can it arise from actions performed without conscious wickedness? Traditional moral philosophy often prioritizes intent, holding individuals accountable for their deliberate choices.

However, Arendt shifted focus to the actions themselves, arguing that even seemingly innocuous deeds can contribute to immense harm within a destructive system. This challenges the notion that only those with evil motives are responsible for evil outcomes.

The discussion continues to shape ethical considerations today.

Challenges to Arendt’s Thesis

Arendt’s concept faced criticism, with some arguing she downplayed Eichmann’s ideological commitment and antisemitism, suggesting a more complex motivation than mere thoughtlessness. Critics contend her focus on bureaucratic function obscured the deeply rooted hatred driving the Holocaust.

Others questioned whether the “banality of evil” excused individual responsibility, implying that anyone could become a perpetrator under the right circumstances. This sparked debate about the limits of situational ethics and the enduring importance of moral agency.

These challenges continue to refine the discussion.

The “Possibility of Evil” in Modern Society

Arendt’s insights resonate today, revealing how bureaucratic indifference and uncritical obedience can normalize harmful actions, fostering environments where evil can flourish.

Contemporary examples demonstrate the dangers of thoughtlessness in political systems and everyday life, demanding constant vigilance.

Bureaucratic Indifference Today

Modern institutions, mirroring the structures Arendt observed, often exhibit a chilling bureaucratic indifference, prioritizing procedure over moral consideration. This manifests in detached decision-making processes, where individuals become cogs in a machine, absolved of personal accountability.

Examples abound – from automated systems denying essential services to impersonal handling of refugee crises – demonstrating how systemic structures can facilitate harm. The focus shifts from the human impact of policies to efficient administration, creating a fertile ground for the “banality of evil” to take root and spread.

This detachment isn’t necessarily malicious intent, but a dangerous erosion of empathy and critical thought within complex organizations.

The Normalization of Harmful Actions

Arendt’s concept highlights how seemingly innocuous actions, when repeated and embedded within a system, can become normalized, obscuring their inherent harm. This gradual acceptance of unethical behavior creates a dangerous precedent, eroding moral boundaries and fostering a climate of complicity.

Contemporary society witnesses this in various forms – from online harassment and disinformation campaigns to discriminatory practices justified as “standard procedure.” The diffusion of responsibility allows individuals to participate in harmful acts without fully confronting their implications.

This normalization is a key component of the “banality of evil,” demonstrating how easily atrocities can occur when critical thinking is suppressed.

The Dangers of Uncritical Obedience

Arendt’s analysis of Eichmann underscored the terrifying potential of uncritical obedience to authority. Individuals, devoid of independent judgment, can become instruments of evil simply by following orders, regardless of their moral implications. This highlights a fundamental flaw in human behavior – the tendency to prioritize conformity over conscience.

Modern parallels exist in bureaucratic structures and hierarchical organizations where questioning authority is discouraged. This can lead to the perpetuation of harmful policies and practices, as individuals abdicate their moral responsibility.

Resisting this requires cultivating critical thinking and a willingness to challenge the status quo.

Expanding the Concept: Beyond Nazi Germany

Arendt’s framework transcends Nazi Germany, offering insights into systemic evil within diverse political systems and historical events, revealing universal patterns of harm.

Applying her ideas illuminates the banality of evil in contemporary conflicts and bureaucratic indifference across various societal structures globally.

Applying the Framework to Other Historical Events

Arendt’s concept extends beyond the Holocaust, offering a lens to examine atrocities like the Armenian Genocide and the Rwandan genocide, revealing similar patterns of bureaucratic implementation.

These events demonstrate how seemingly ordinary individuals, operating within established systems, can contribute to mass violence through thoughtlessness and obedience to authority.

Analyzing these historical tragedies through the “banality of evil” highlights the dangers of unchecked power and the crucial need for individual moral responsibility, even within oppressive regimes.

It underscores that evil isn’t solely perpetrated by monstrous figures, but can arise from the normalization of harmful actions within systemic structures.

The Banality of Evil in Political Systems

Arendt’s framework illuminates how seemingly rational political processes can facilitate immense harm, as seen in totalitarian regimes and authoritarian states globally.

The “banality of evil” manifests in the bureaucratic structures that enable oppression, where individuals fulfill their roles without critically examining the moral implications of their actions.

This extends to modern political systems, where policies and procedures can perpetuate injustice through detached administration and a lack of individual accountability.

Understanding this dynamic is crucial for recognizing and resisting the normalization of harmful practices within political institutions.

Examples in Contemporary Conflicts

Arendt’s concept resonates in modern conflicts, where drone warfare exemplifies detached violence carried out by individuals distanced from its consequences.

Similarly, the use of algorithms in surveillance and targeted interventions can perpetuate systemic biases and injustices, demonstrating “banality of evil” in action.

The bureaucratic processes within military organizations and intelligence agencies can also foster a climate of thoughtlessness, enabling harmful actions to occur.

These examples highlight the enduring relevance of Arendt’s work in understanding the mechanisms of evil in the 21st century.

Philosophical Implications

Arendt’s work profoundly impacts moral philosophy, questioning the nature of judgment and the roots of evil, urging critical self-reflection and challenging traditional ethics.

It forces us to confront the unsettling possibility that evil isn’t a rare aberration, but a potential within us all.

The Nature of Moral Judgment

Arendt’s concept fundamentally alters how we perceive moral judgment, shifting focus from pre-defined rules to the capacity for thinking what we are doing.

She argues that evil deeds aren’t necessarily committed by inherently wicked people, but by individuals who abdicate their responsibility to think critically and judge independently.

This “thoughtlessness” isn’t stupidity, but a failure to engage with the world and consider the consequences of one’s actions, leading to participation in systemic harm.

Moral judgment, therefore, isn’t about applying abstract principles, but about actively engaging in a continuous process of evaluation and discernment.

The Problem of Evil in Philosophy

Arendt’s work re-frames the traditional “problem of evil” – often posed as a theological dilemma – as a distinctly political and human one.

Rather than seeking to explain the origin of evil in a cosmic sense, she focuses on the conditions that allow it to manifest within human societies and through individual actions.

Her concept challenges the notion of evil as a radical, exceptional force, suggesting it’s disturbingly commonplace and rooted in the everyday failures of judgment.

This perspective demands a re-evaluation of philosophical approaches to morality, emphasizing the importance of political action and critical thinking.

The Importance of Critical Thinking

Arendt’s analysis underscores the vital role of critical thinking as a bulwark against the “banality of evil.” Thoughtlessness – the inability or unwillingness to engage in independent judgment – is identified as a key facilitator of horrific acts.

She argues that individuals must actively question authority, challenge norms, and cultivate a capacity for discerning right from wrong, even in ambiguous situations.

This isn’t merely an intellectual exercise, but a moral imperative, essential for preventing complicity in systemic injustice and safeguarding democratic values.

The Relevance of Arendt’s Work Today

Arendt’s insights remain profoundly relevant, urging vigilance against bureaucratic indifference and uncritical obedience in contemporary society, preventing future atrocities through awareness.

Lessons for Preventing Future Atrocities

Arendt’s work powerfully demonstrates that preventing atrocities requires fostering a culture of critical thinking and individual responsibility, actively resisting the allure of thoughtlessness.

Recognizing the “banality of evil” necessitates challenging systemic structures that enable harmful actions and promoting moral courage to question authority.

Cultivating empathy and understanding the dangers of bureaucratic normalization are crucial steps towards safeguarding against future horrors, demanding constant vigilance and proactive intervention.

Ultimately, Arendt’s legacy calls for a commitment to ethical engagement and a refusal to accept harmful actions as simply “following orders.”

The Need for Individual Responsibility

Arendt’s analysis underscores that individual responsibility isn’t diminished by systemic factors, but rather amplified within them; each person possesses the capacity for judgment and moral action.

The “banality of evil” isn’t an excuse for inaction, but a stark warning against the dangers of thoughtlessness and uncritical obedience to authority.

Rejecting the comfort of conformity and embracing the burden of moral discernment are essential for preventing complicity in harmful acts, demanding proactive ethical engagement.

Ultimately, Arendt’s work champions the power of individual conscience as a vital safeguard against the normalization of evil.

Combating Thoughtlessness in Public Discourse

Arendt’s work highlights the crucial role of critical thinking in resisting the allure of ideological narratives and preventing the normalization of harmful actions within society.

Fostering a public sphere that values reasoned debate, encourages questioning assumptions, and prioritizes nuanced understanding is vital for combating thoughtlessness.

Promoting intellectual humility and a willingness to engage with diverse perspectives can disrupt echo chambers and cultivate a more informed citizenry.

Active participation in public discourse, grounded in ethical reflection, is essential for safeguarding against the “banality of evil”.

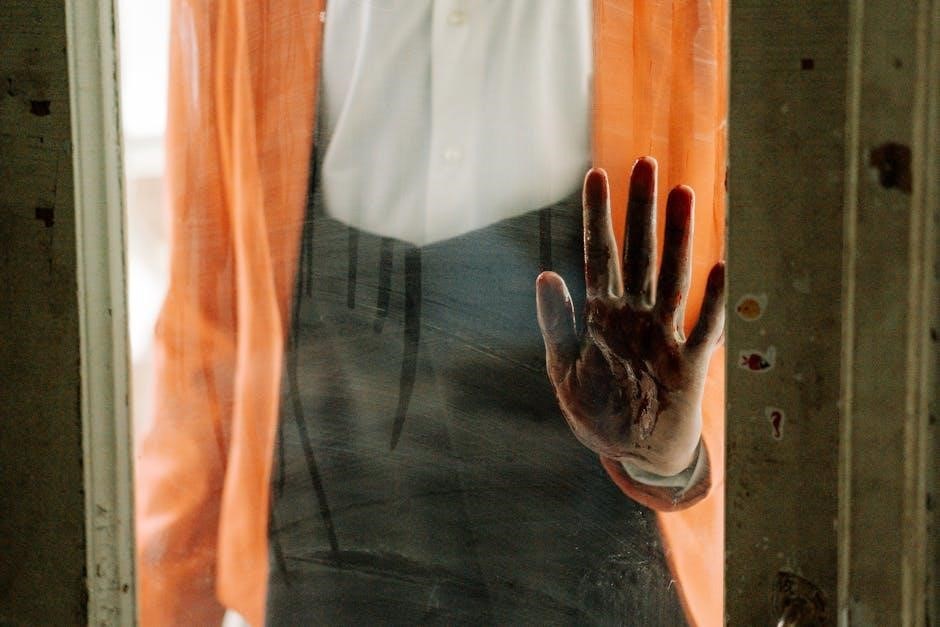

“The Possibility of Evil” as a Literary Theme

Fiction and film powerfully explore Arendt’s ideas, portraying how ordinary people succumb to evil through indifference or obedience, revealing its unsettling potential.

Artistic representations illuminate the dangers of thoughtlessness and the importance of moral courage in confronting systemic injustice and challenging harmful norms.

Exploring Evil in Fiction and Film

Literary and cinematic works frequently grapple with Arendt’s concept, showcasing characters who participate in evil not through grand malice, but through bureaucratic processes or simple obedience.

Examples abound, from depictions of Nazi collaborators to portrayals of individuals blindly following orders in oppressive regimes, illustrating the “banality of evil” in action.

These narratives often emphasize the importance of individual conscience and the dangers of unchecked authority, prompting audiences to question their own potential for complicity.

Films like Schindler’s List and novels exploring totalitarian systems demonstrate how seemingly ordinary people can contribute to extraordinary horrors, echoing Arendt’s insights.

Representations of Arendt’s Ideas in Art

Visual arts offer a powerful medium for exploring the abstract concepts within Arendt’s work, particularly the unsettling nature of “the banality of evil.”

Artists have responded to her ideas through depictions of bureaucratic landscapes, faceless crowds, and individuals seemingly detached from the consequences of their actions.

These artistic representations often aim to provoke discomfort and encourage viewers to confront the potential for evil within everyday life and societal structures.

Contemporary installations and paintings frequently utilize symbolism to convey the themes of thoughtlessness, obedience, and the normalization of harmful behaviors, mirroring Arendt’s analysis.

The Power of Storytelling to Illuminate Evil

Narratives, both fictional and documentary, possess a unique capacity to humanize the complexities of evil, moving beyond abstract philosophical concepts.

Literature and film can vividly portray the psychological processes and societal conditions that enable individuals to participate in horrific acts, echoing Arendt’s insights.

By presenting compelling characters and intricate plots, storytelling fosters empathy and encourages critical reflection on moral responsibility and the dangers of conformity.

Artful storytelling allows audiences to grapple with the unsettling truth that evil isn’t always perpetrated by monstrous figures, but can arise from ordinary people.

Further Research and Resources

Explore Arendt’s core texts like “Eichmann in Jerusalem” and related scholarly analyses for deeper understanding.

Numerous articles and documentaries on the Eichmann trial offer valuable context and diverse perspectives on her theories.

Key Texts by Hannah Arendt

Essential for comprehending Arendt’s concepts is “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil” (1963), detailing the trial and introducing her central thesis.

“The Origins of Totalitarianism” (1951) provides crucial background, examining the conditions enabling mass atrocities and the erosion of political freedoms.

“The Human Condition” (1958) explores the fundamental categories of human existence – labor, work, and action – informing her views on moral agency.

“Responsibility and Judgment” (2003, posthumous) further develops her ideas on political action and the importance of critical thinking.

Scholarly Articles and Books

Expanding on Arendt’s work, numerous scholars have explored the “banality of evil.” Elizabeth Young’s “Habit, Irony, and Accommodation: Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem” (1994) offers a critical analysis.

Seyla Benhabib’s “The Reluctant Modernism of Hannah Arendt” (1996) contextualizes Arendt’s thought within broader philosophical traditions.

For a collection of essays, consider “Hannah Arendt: Twenty-First Century Perspectives” (2018), providing contemporary interpretations.

Further research can be found in journals like Political Theory and The Review of Politics.

Documentaries and Films on the Eichmann Trial

Visual documentation provides crucial context for understanding Arendt’s observations. “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil” (1961), though a book, inspired several adaptations.

The original courtroom footage from the Eichmann trial itself is invaluable, offering a direct glimpse into the proceedings and Eichmann’s demeanor.

Documentaries analyzing the trial, such as those featured on historical channels, often incorporate Arendt’s analysis and expert commentary.

These resources illuminate the complexities of the event and Arendt’s controversial conclusions;

The Ongoing Challenge

Arendt’s work serves as a persistent warning: vigilance against thoughtlessness and uncritical obedience is crucial to prevent future atrocities and uphold moral responsibility.

The Persistent Threat of Evil

The enduring relevance of Arendt’s concept lies in recognizing that the potential for evil isn’t confined to historical atrocities like the Holocaust; it remains a constant possibility within human affairs.

Bureaucratic systems, while often intended for efficiency, can inadvertently facilitate harmful actions when individuals abdicate their moral judgment and engage in unthinking obedience.

This threat isn’t limited to grand schemes, but manifests in everyday indifference and the normalization of harmful behaviors, demanding continuous self-reflection and critical engagement.

The Importance of Vigilance

Arendt’s work underscores the necessity of constant vigilance against the insidious creep of thoughtlessness and the dangers of unquestioning acceptance of authority.

Cultivating a habit of critical thinking, questioning norms, and actively engaging with moral implications are crucial safeguards against the normalization of harmful actions.

Remaining alert to the potential for evil requires a commitment to individual responsibility and a willingness to challenge systems that may inadvertently enable injustice and suffering.

A Call to Moral Action

Arendt’s analysis isn’t a descent into despair, but a powerful call to proactive moral engagement; it demands resisting the allure of conformity and embracing the discomfort of independent judgment.

We must actively cultivate a sense of personal accountability, refusing to become mere cogs in systems that perpetuate harm, and championing ethical considerations in all spheres of life.

Responding to the “possibility of evil” necessitates courage, empathy, and a steadfast commitment to defending human dignity against the forces of indifference and oppression.